At the southern end of Anzac cove, a concrete bunker lies blasted and crippled, tilted on an angle and lapping in the water, its sides pockmarked by bullets. I climbed into its claustrophobic cell, crouched and peered through the narrow gun slot. In front of me panned the sparkling blue water of the Aegean Sea, a strip of sand, and the steep cliffs and ridges above. It was a beautiful setting, an ideal place for a resort – if it wasn’t a cemetery reserve.

At the southern end of Anzac cove, a concrete bunker lies blasted and crippled, tilted on an angle and lapping in the water, its sides pockmarked by bullets. I climbed into its claustrophobic cell, crouched and peered through the narrow gun slot. In front of me panned the sparkling blue water of the Aegean Sea, a strip of sand, and the steep cliffs and ridges above. It was a beautiful setting, an ideal place for a resort – if it wasn’t a cemetery reserve.

Peering through the bunkers slot was like viewing through an old camera and soon my head was full of visions. I could see the boats landing over 90 years earlier in the morning mist. I could hear the ‘whomp’ of explosions and the bullets whistling around like 10,000 whipbirds. The first wave of 1500 Allied troops was supposed to triumphantly sweep up the hills to Chanuk Bair with no resistance, but thousands of Turkish troops were huddled in wait. In the newsreel in my head, Aussie diggers jump out of the boats, hoping the breath they just took was not their last. They clamber for the small sand dune twenty feet from the water, just high enough to shield them from the shower of deadly metal raining down at an acute angle. The first arrivals press into the sand wall, pulling the next in closer. The ones four deep are exposed and being cut down, shrieking a death cry as their mates release their hands. These boys all became men before they ever stopped being boys.

I later joined my wife and two small kids and we climbed through the hillside trenches, the distance between them so close the enemies could have almost lit each other’s cigarettes. As we were there, a tour bus unloaded Turks into the trench opposite, and in a surreal re- enactment, I looked across the tiny divide into their brown eyes. Over 8,000 Aussies died here, but previously unknown to me, 80,000 Turks also died defending their homeland. From their trench, the Turkish group broke into broad grins, gave the thumbs up and cried ‘Aussie, Aussie, Aussie’ as though we were at a football game together. They soon turned to go to the graveyards of their ancestors who were killed by mine. I turned to visit the graves of my people that were killed by theirs. And yet we have become friends.

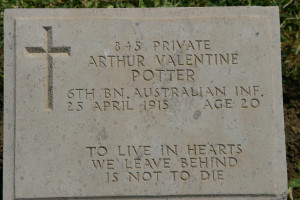

At Lone Pine cemetery, gleaming white burial plaques stretch out across the manicured grass, vast numbers dating the lads that died on 25 April 1915 – Anzac Day. I had heard that Gallipoli could emotionally gut even the hardiest of souls, but I had not expected it to affect me. After all, I had no direct lineage to events here. But what sucked the breath from my lungs was the familiarity of the surnames in this distant place. Jones, McDonald, Foster, Smith. These names from my school class photos leapt up from the plaques, destroying any pre-conceived notion of mine that Gallipoli was a distant story about old men, told in black-and-white documentaries. It was about boys, like me and my mates had once been, who had gone off on an adventure of greatness with romantic recruitment promises to ‘see the world’ and ‘meet French girls’ – all wasted, all dead. To lie here in the soil. Forever Young.

The final impact came when another long-buried memory exploded in my head. I am nine years-old, swinging my arms and rushing to keep pace with my father. His World War 2 medals are pinned to my chest. I am saluting proudly as we march past the applauding Anzac Day crowds. My Dad had been a private, a sapper. He died when I was seventeen. Cancer, the English language’s worst word. I had adopted a lock-down mentality to get through the loss, and for over twenty-five years had successfully buried those memories with him, until now, when one particular headstone drew me into silence. It was the headstone of Private Arthur Valentine Potter, 6th Battalion, Australian Infantry. Died 25 April 1915, age twenty. Its inscription said:

To live in hearts

We leave behind

Is not to die

Man, had I failed my father at that! The kids came running towards me yelling ‘Daddy!’ and I smiled at them through tears, knowing the power of travel had just helped me discover a magic new way of remembering my father with happiness. And I hoped with all my breath that, after I was gone, my kids would do the same.

As we left Gallipoli, we passed Turkish General Ataturk’s famous 1934 tribute he wrote for the ANZACS killed here, carved into rock at the landing beach. Its final lines stated:

You, the mothers, who sent their sons from far away countries wipe away your tears; your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land they have become our sons as well.

The juxtaposition of our lives versus those past was never clearer. Here we were, meandering lazily with our children, from country to country, like rich colonials, but if we had been born in another time, or even another place right now, we could be fighting, starving or dead.

Truly, we still live in a lucky country. Lest we forget.

Adjusted extract from the book On The Road With Kids by John Ahern. Published late 2014 by Pan Macmillan.